NEWS

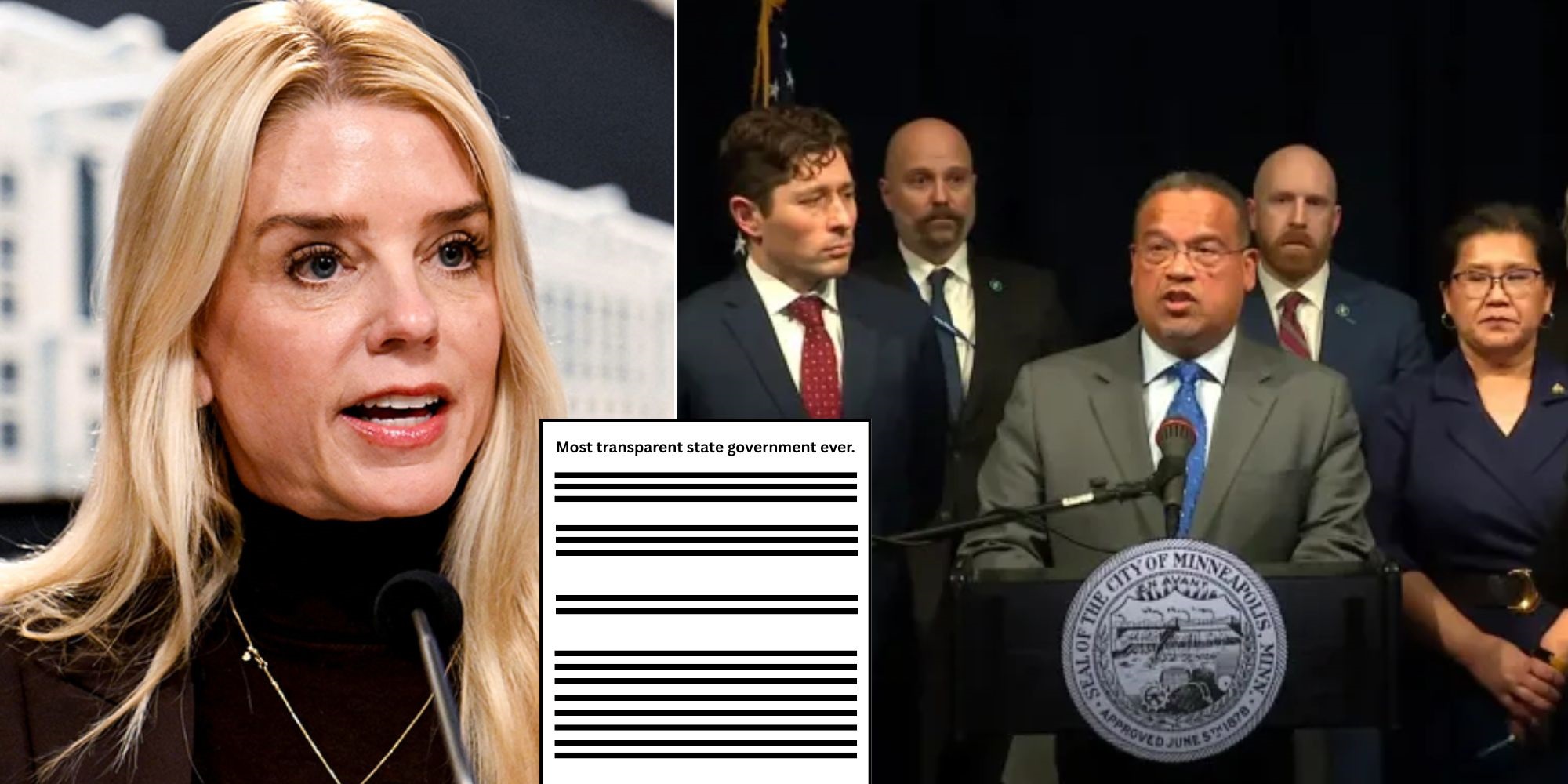

BREAKING: After Pam Bondi requested Minnesota’s voter data, MN officials reportedly sent her exactly 1% of their records with it all blacked out and a note on the top of every page that says, “Most transparent state government ever.”

What Minnesota sent back was not what Pam Bondi was expecting.

After the former Florida attorney general formally requested Minnesota’s voter data, state officials reportedly complied — technically. But instead of handing over a full trove of records, Minnesota sent just one percent of the data, with every single line blacked out. Across the top of every page was the same unmistakable message, stamped like a signature of defiance: “Most transparent state government ever.”

The response immediately ignited political shockwaves.

At face value, Minnesota followed the request. Data was sent. Pages were delivered. The box was checked. But the substance was gone, replaced by thick black redactions and a note that many interpreted as sarcastic, even confrontational. To supporters of the state’s leadership, it was a pointed stand for privacy, state authority, and resistance to what they see as federal overreach. To critics, it was a blatant act of obstruction, bordering on mockery.

The tension did not arise in a vacuum. Requests for voter data have become one of the most sensitive battlegrounds in modern American politics. Supporters argue they are necessary for election integrity and transparency. Opponents warn they can be weaponized to intimidate voters, undermine trust, or target specific communities. Minnesota officials have long positioned themselves firmly in the latter camp, emphasizing strict data protection laws and aggressive safeguards around voter information.

This latest move appears to be the clearest signal yet of where the state draws its line.

According to people familiar with the exchange, Minnesota officials intentionally limited the data to a symbolic fraction and ensured it was unusable, while still technically responding. The message printed on every page was no accident. It was designed to be seen, shared, and interpreted — a political statement wrapped in bureaucratic compliance.

Reaction was swift and fierce.

Conservative voices accused Minnesota of acting in bad faith, arguing that the state is deliberately shielding information that should be publicly accessible and accountable. Some called for legal action, claiming the response could violate federal expectations or set a dangerous precedent where states openly defy lawful requests with sarcasm instead of substance.

On the other side, civil rights advocates and state officials applauded the move as a clever and necessary defense. They argue that voter data is not a political toy and that Minnesota is sending a clear warning: requests perceived as partisan or intrusive will not be welcomed with open files. To them, the blacked-out pages represent a firewall — not a joke.

Behind the scenes, the episode highlights a growing fracture between states and federal or national political figures over control of election systems. States run elections. States collect voter data. And increasingly, states are refusing to hand over that information without a fight.

What makes this moment especially striking is the tone. Minnesota didn’t just say no. It didn’t quietly delay. It responded with paperwork that spoke louder than any press conference. The phrase “Most transparent state government ever” now circulates widely, interpreted by some as biting satire and by others as open provocation.

The question now is what comes next.

Will Bondi escalate the dispute through legal channels? Will federal authorities push harder, using courts to force compliance? Or will this episode become another symbol in a growing catalog of state-level resistance to national political pressure?

For Minnesota, the message is already clear. Transparency, in their view, does not mean surrender. And compliance, they’ve shown, does not have to be cooperative.

In a political climate where even paperwork can feel like a protest, a stack of blacked-out pages may say more than a thousand unredacted ones.